What It Means to Be a Black, Indigenous, Latino

- Mani-Jade Garcia

- Jun 28, 2020

- 10 min read

Updated: Aug 5, 2021

This story has been donated to the New-York Historical Society's History Responds initiative.

Growing up my father’s favorite nickname for me was “ni--er”, next only to Kunta Kinte.

As the darkest person in our Puerto Rican nuclear family (on both sides) the dark color of my skin was under constant discussion, constant ridicule. While my father’s behavior was and still is very troubling to me, I have always loved the color of my skin. I accepted that I was Black at a very young age because the world told me that it was important to accept that I am Black. I did not know at the time how super-charged that word is. It has only ever bothered me how much it bothered so many people around me that I was Black. It still does. For years I believed that I was adopted and that my real parents, an old Black couple with kind faces that smelled of cocoa butter—that I can still see so vividly in my imagination—would come pick me up one day in a ‘57 Chevy. The idea still comforts me. (I have no idea why a ‘57 Chevy. So be it.). I did see a picture once, of my 7-foot-tall, African (I am not sure how many generations before me) grandfather who had the most beautiful BLACK skin. He was darker than me, and I loved it.

I list Indigenous between Black and Latino when describing my identity because although it is the identity that is most mysterious to me—I experience that identity deepest in my core, always pulsing—calling to me. Maybe it is this mystery—a result of the rape, and genocide of the Arawak and Taino people that occupied the island that would be named Puerto Rico by colonizers—that makes my indigenous identity feel so deeply buried inside of me. Perhaps the night filled with spiritual phenomena that I spent with my Taino great-grandmother when I was a kid (she lived to be 105) left some of that deep impression on my soul. Recently, distressed that I had never known her name, I called out to my great-grandmother to ask her name. That night I heard a voice whisper what sounded like, “Ayoktol.” I don’t question the pulsing when it speaks. Her name was or I should say is Ayoktol. The mass genocide of the indigenous Arawak and Taino people who occupied the land now called the Caribbean and Antilles; and of the indigenous people of the land that is now called ‘The Americas’ is a story that remains largely untold and wildly understated —anesthetized intentionally from the consciousness of Europeans and their super violent offspring—the Americans. I highly recommend that everyone innervate their consciousness by reading “Tainos and Caribs: The Aboriginal Cultures of the Antilles” by Sebastián Robiou Lamarche and “An Indigenous Peoples' History of the United States” by Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz.

For years I believed that I was adopted and that my real parents, an old Black couple with kind faces that smelled of cocoa butter—that I can still see so vividly in my imagination—would come pick me up one day in a ‘57 Chevy.

Finally, although my genetic heritage includes Spanish slave traders who committed heinous acts like rape, looting, and murder, I do not relate AT ALL personally to Europe and its colonization of the world. “Hispanic” in popular use, in my opinion, is a claim to Europe and to Whiteness (and the dangerous myth of European exceptionalism) that has zero appeal to me. I actually find the popular use of the word, especially among Anti-Black Spanish speaking people, quite loathsome! Also, I grew up in Alamogordo, New Mexico around Mexicans, far away from Puerto Rican culture, food, and language. So, I relate much more to “Latino” people and culture. And of course, I love my boricuas! Identity is not laden with mutual exclusives. Despite the seeming connotations of poverty and worthlessness in the popular use of “Latino,” I am most comfortable identifying as Latino, to honor my connection to Spanish speaking people and our cultures—and our languages. Spanish—New Mexico Nuyorican flavored—is my first language. In fact, I spoke only Spanish until I attended school, and it was beaten out of me—and news anchor level accentless English beaten into me. That experience, along with other severe traumas that occurred in the context of Spanish-speaking people, makes Spanish an emotionally loaded language for me to this day. The sound of native Spanish speakers causes equally strong feelings of comfort and discomfort in me. It is a strange feeling to try and describe. For a more thorough discussion of the terms “Hispanic” and “Latino”, I recommend starting with “‘Hispanic" and ’Latino’: The Viability of Categories for Panethnic Unity” by José Calderón.

There has always been a need to confront systemic racism. Always!

That said, I have mixed feelings about any type of terminology in popular use that dehumanizes racism. What I mean when I use the word dehumanize right now is: to make mechanical in our personal ontology of the world. Systems are created, maintained, and guarded by people. And so, it is people and the racism that lives in their minds, hearts, and souls (explicit and implicit) that I am most interested in confronting. What I mean by ontology is how we, as individuals and by extension, groups determine what is true and real—and what is not true and not real—about life and the world. Ontology is the DNA of belief. And belief determines all human behavior. If it is true, hypothetically, that White people are exceptional, then anything White people do is interpreted through the lens of a belief system that perpetuates a “truth” that they are exceptional. This is why, for example, a person like Dylann Roof can enter a Black Church, kill 9 innocent people, live to tell the police he is hungry, and allegedly have those same police officers bring him food from Burger King as a response.

Several years ago, I was falsely accused by a white female roommate of threatening her life with a gun. Having lost a close friend to gun violence (while I was at his house) at a very young age, I do not and have never possessed a gun. Guns terrify me! Violence towards women is abhorrent and ALWAYS inexcusable to me! Also, to clarify, what I did threaten, during a bad argument, was to expose her sale of dangerous prescription medication to fellow students. Despite this TRUTH — and the TRUTH of the involved police officers’ repeated acknowledgements that there was zero evidence of her accusations — I was arrested, assaulted, tortured, jailed, and starved for two days. It is not hard for a police officer to maintain as “truth”, against all evidence, that I, a Black man (in their 1D perceptual estimation) in a National Science Foundation-funded master’s degree program at the time, possess and would use a gun on another person. Except, nothing about it was and ever will be true! Compare that with the TRUTH that a blonde young man who looks like their nephew or son casually murdered 9 people; the only explanation police officers can arrive at is that he is an exception, a violent “lone wolf,” which in popular American culture is a sympathetic character that is coddled, pitied, protected, fed, and even loved.

Yes, White Exceptionalism is a double-edged semantic sword.

Let’s add scarcity to the equation now. I highly recommend that everyone read the book, “Scarcity: Why Having Too Little Means So Much” by Sendhil Mullainathan and Eldar Shafir. Take any of my identities and scarcity is a reality from birth to death—in EVERY. SINGLE. THING. ON. EVERY. SINGLE. DAY. In discussions of racism we tend to focus on material scarcity, and that is critical. But that is not the whole picture, not even close. I am more interested in the non-material scarcity that leads to material scarcity. Consider, for example, the human need for emotional support: a shoulder to cry on; loved ones who remember your important days—whether those are days of celebration or grief; being granted the benefit of the doubt; having people that will drop everything to care for you; and all the other things that contribute to emotional health and happiness.

I am now going to use the term White. A “White” person, as popularly defined in the United States Census, is one “having origins in any of the original peoples of Europe, the Middle East, or North Africa”. That is different from the idea of Whiteness, and the people who subscribe to it, who I refer to as White people.

Whiteness is an idea created, propagated, and defended by a subset of extremely violent and persistent people (mostly men) who happen to have light-colored skin due to natural genetic variation.

I have VERY close, safe, loving relationships with people who have light-colored or “white” skin. I am not referring to them, or anyone else who happens to have been born “light-skinned” or ticks the box next to “White” in the Census, in what I write next. And it disgusts me every time I, for the sake of clarity, find myself needing to refer to them by the color of their skin. This is not merely about skin. It is about minds, hearts, and souls. It is about power and dominance. It is about decisions people make about what to believe and hold as true. It is about ontology. You can totally respond that you’re “White” in the Census but completely dissociate yourself with the idea of Whiteness. On the other hand, there are some people with darker skin who submit themselves to Whiteness. Anyway, it is worth noting that people with light-colored skin, due to genetics, do benefit greatly from the widespread myth of Whiteness, whether they are aware of it or not. So, it is important that people with light-colored skin pay close attention.

Whiteness is a carefully programmed social delusion. It is a social construct, a mythical category of people who have a God-given social, spiritual, and legal right to ownership of whatever they want: land, people, ideas, morality, belief, knowledge, even life itself. Whiteness is an idea created, propagated, and defended by a subset of extremely violent and persistent people (mostly men) who happen to have light-colored skin due to natural genetic variation. White people behave as if they consider emotional support a right—not a gift— and specifically, a right only for White people. In contrast, emotional support for Non-White people from White people is considered a gift. This is a recipe for a high risk of scarcity for Non-White people in all of their relationships with White people.

Emotional support is work. It involves “holding space” as people sometimes say, for another person to consume your time; your energy; maybe your physical space; maybe your financial space; definitely your cognitive, emotional, and spiritual space. Every person has finite amounts of all these things. And every person within a given social circle must determine how to balance “holding space” for others with their own capacity to give and their own needs for emotional support.

To White people, the other White people in their lives—ESPECIALLY White men—have an inalienable right to emotional support. It doesn’t matter, for example, if their fathers, or brothers, or friends, colleagues, or even their ex-lovers have abused them or do abuse them—or that is to say, it doesn’t matter if love can be ruled out as a primary motivating factor. This reality can create enormous pressure for people who happen to have light-colored skin but do not identify as White, as defined above—since some of their fathers, or brothers, or friends, or colleagues, or even their ex-lovers are White men (implicitly or explicitly).

White men have convinced the world that emotional support is their right, and the world knows how angry and violent White men can instantly become about their perceived rights. Therefore, any social circle that includes White men (by choice or force of circumstances) is at high risk for scarcity, especially for any Black members who happen to be in the same social circle (by choice or force of circumstances). With some rare exceptions, White men do not know what it means to go without. Most cannot tolerate the idea, much less the experience of scarcity, especially when it comes to emotional support.

There is nothing more fragile in this world than a fragile White man—and that is, tragically, most of them.

There is nothing more fragile in this world than a fragile White man—and that is, tragically, most of them. Fragility is the karma for their crimes, and for their deliberate ignorance. This reality creates overtaxed social systems, with an inordinate amount of “held space” on permanent reserve for White men—regardless of who they are and what they are doing or not doing to contribute to the collective resources for emotional support. Paradoxically, in my relationship experiences, the less White men contribute to collective resources for emotional support—often—the MORE space is held for them. For this reason, the vast majority of White men are black holes of emotional support, draining everything and every person around them. Maybe White-Holes is a better term. And I will have to write about the emotional support demands of White Women another time. I will have to write that piece with Black women.

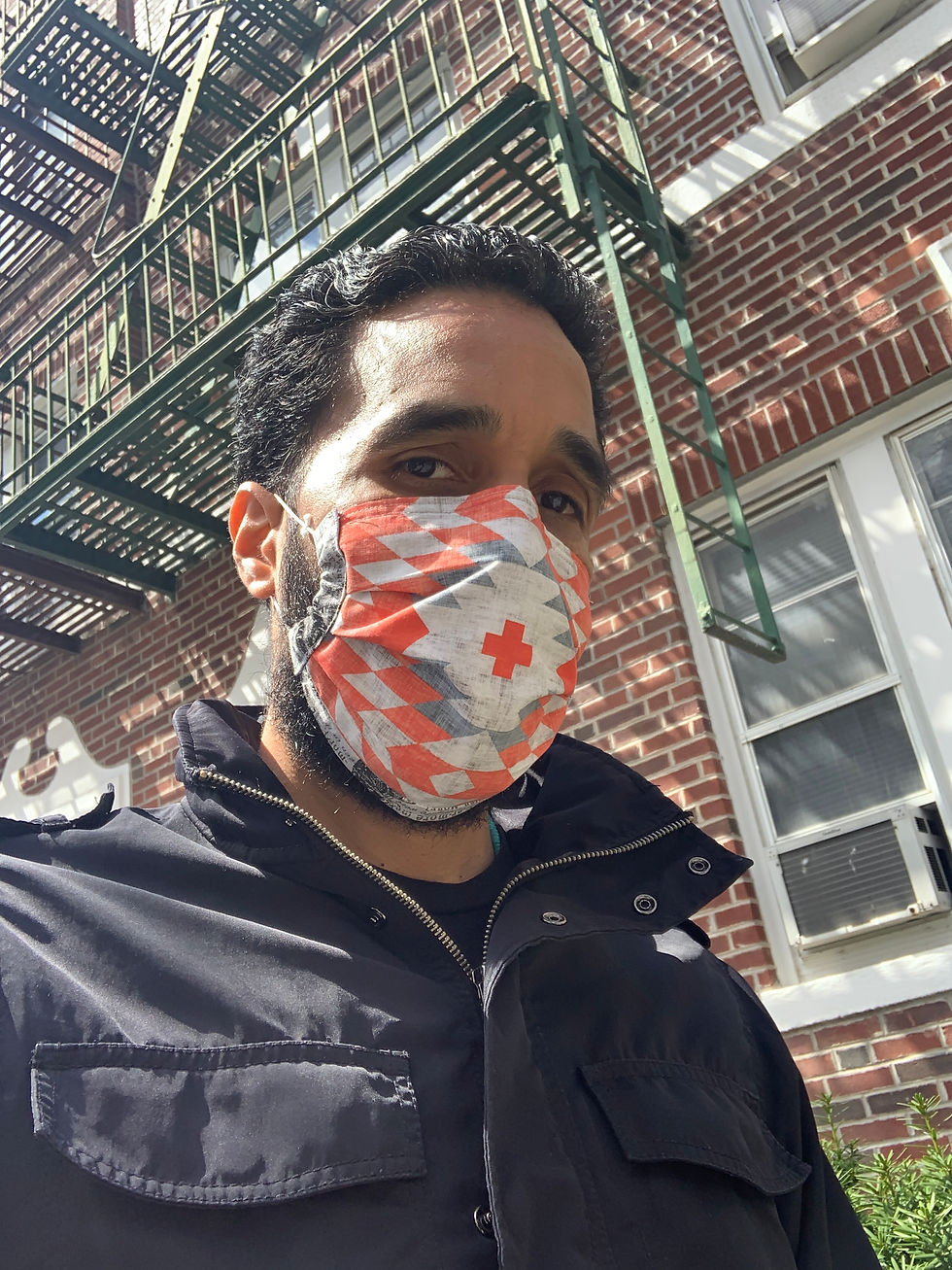

White people often cannot fathom what it is like, as a non-White person in the context of a social group including one or more White-Holes, to experience the very normative need for emotional support. Expressing the need is walking through a field full of landmines. Suppressing the need is psychological torture and leads to scores of physical, spiritual, and mental health problems. This is particularly true during times of extreme stress, where scarcity is imposed on a social circle by outside forces—such as currently during the COVID-19 pandemic. What could be more infuriating than a person asking for a “gift” of emotional support when everyone is strapped and yet still, even more than usual, anxiously attending to the “right” for emotional support of the community White-Holes?!

The net effect of this reality on people like me, a Black-Indigenous-Latino, is a life with a high risk of loneliness, isolation, and chronically unmet needs. It is why far too many Black people spend potentially important days like Juneteenth alone and without emotional support. It is why Father’s Day and Mother’s Day can be both a day of pride and fear. It is why “holidays” and “special occasions” may be especially distressing to so many Non-White people, as they are to me.

Sure, we Non-White people do our best to support each other, and many of us are the most strapped in our social circles that by choice, chance, or force include White-Holes. So, a lot…and by a lot I mean MOST…of our emotional life is experienced alone. Alone perhaps, during these COVID-19 pandemic days, in a public laundry room next to maskless White men who don’t know the meaning of 6 feet of distance (my experience this Juneteenth/Father’s Day Weekend). It is why we miss work, miss deadlines, miss opportunities, lose jobs, lose relationships, lose our minds, and far too often lose our lives.

This is my experience. The experiences of others, most likely, are different. You should ask them.